World of Tanks news » History Spotlight: Dogs of War

Man is not the only snarling beast to take the field during times of war. In 1942 the American Kennel Association with the help of another group named Dogs for Defense began a campaign to have the American people volunteer their canine companions for active duty.

Dogs have been a part of nearly every military in history, but prior to this movement the US forces had not developed this resource on such a large scale (though they did have some dogs already in service). The US would train 10,000 dogs for duty during WW2, which paled in comparison to the 200,000 dogs that Germany is thought to have trained by the time the US entered the war.

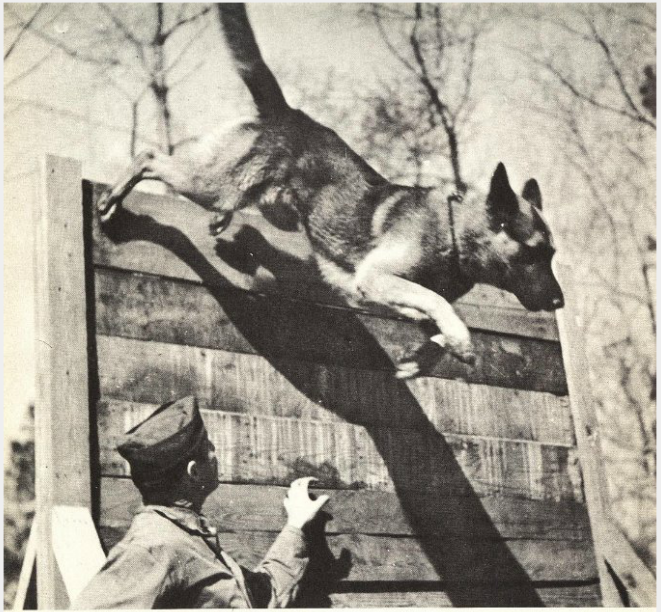

The American volunteer response was so swift that by March of that same year the Quartermaster Corps began inducting dogs as service animals. Their training was completed at numerous special camps across the US. There was some initial difficulty in structuring how and where these dogs received their training, but they were eventually schooled for duty as Sentry, Scout/Reconnaissance, Sled & Pack, Messenger, or Mine Detection dogs.

These K-9 Soldiers were deployed on every front; Europe, North Africa, and the Pacific. The dogs ran dispatches between units when normal communications were disrupted. They assisted in locating and even hauling wounded GIs. They carried ammunition and medical supplies to troops in need during combat. Their small size and low profile aided in their usefulness and success rate in these tasks.

One of the more infamous roles that dogs played for the Allied forces was that of demolition and anti-tank. In Russia, some dogs were trained to dive under enemy tanks while carrying a satchel of explosives. The US also considered using dogs against bunkers with a similar method. These missions were one way trips for our furry allies. Eventually both uses were deemed to be too high risk. The Russian AT dogs met with limited success partly due to the fact that they were trained using Russian tanks that were diesel powered, so the German tanks, primarily using gasoline engines, smelled differently and confused the dog’s keen noses. The dogs were unreliable in delivering the charges to their targets while under fire, and some were known to return to their handlers with live explosives in tow.

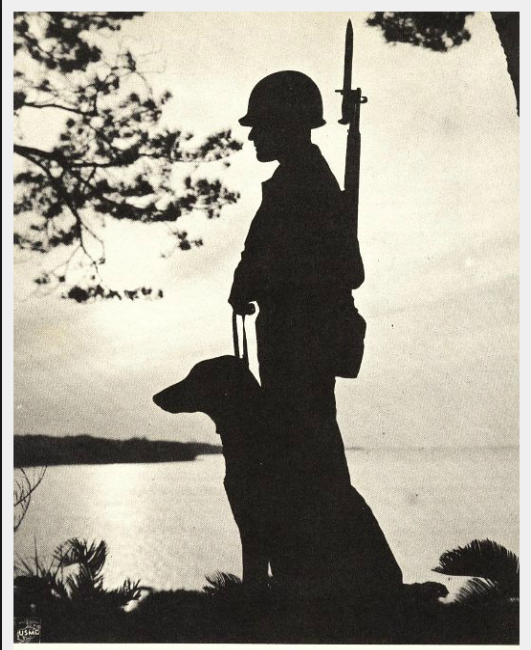

The K-9 units were probably most adept in the roles of Scout and Sentry. In the Pacific theater the US troops faced an entrenched and often times well hidden enemy. The dense vegetation and topography made visual detection a challenge without modern technology like satellite imaging or infrared. With a well-trained scout dog and handler taking point, a patrol would be alerted to enemy movement and any ambushes. Some dogs were even trained to detect booby traps like trip wires and pitfalls. It’s been recorded that no patrol that had a scout dog ever came under fire without at least a few moments notice. The dogs and their handlers gained valuable field intelligence during every maneuver. These dogs are credited with saving countless infantry lives.

The GIs valued these dogs a great deal, and even went so far as to award them company citations for heroism. A number of dogs received combat medals such as the Purple Heart, but these were later rescinded when the War Department restricted these awards to humans. The pad-footed patriots were officially recognized for their service, eventually. The QMC released certificates for dogs that were discharged from service or were killed in action.

When the war ended and the troops returned home there was some concern about what would become of the dogs. Not all of their owners were in a position to welcome them back. There were also a large number of dogs that were drafted into service from pounds and didn’t have any owners to return to. However, thanks to the Quartermaster Corps and the Dogs for Defense, every dog was put through a processing station in the hope that they’d be able to return to civilian life. Sadly, a small number of dogs were suffering from combat stress or were otherwise deemed unfit to be repatriated; after attempts to rehabilitate them failed they were euthanized.

Once the public was alerted to the fact that there were surplus dogs looking for a home the influx of requests for adoption was staggering. Over 17,000 applications arrived, vastly more than the number of dogs available, and the requests continued to arrive years after all of the dogs were accounted for.

Each dog was awarded a certificate of faithful service and honorable discharge. Every dog was shipped to their owner at the government’s expense, and all were given a kit consisting of their awards, a collar, a leash, and a copy of the War Department manual War Dogs. Once home, the soldiers, both man and hound, kicked the mud from their feet and bottled that ferocity they unleashed overseas, knowing that their courage and sacrifices had earned themselves and their countrymen, at last and at least, a few quieter days.

Update comments

Update comments