World of Tanks news » The Chieftain's Hatch: What's in a Name?

Those of you who have been following my writings and activities either in the Hatch or on the forums should have figured out by now that I’m more cynical than most. I don’t normally subscribe to the common consensus just because it’s common consensus; I prefer to see a primary reference, or at least a direct connection to one. However, even I will break that rule on occasion. There are some things that, though I’ve never seen anything definitive, I will accept at face value just because it’s the way it’s always been known for generations and who am I to say different? One of these stipulations is the fact that American tank names like “Sherman” or “Hellcat” never received War Department or Army Ordnance approval. Well, I’ve just received another lesson on assumptions. Actually, it's the same lesson I’ve had before. I just keep refusing to learn from it.

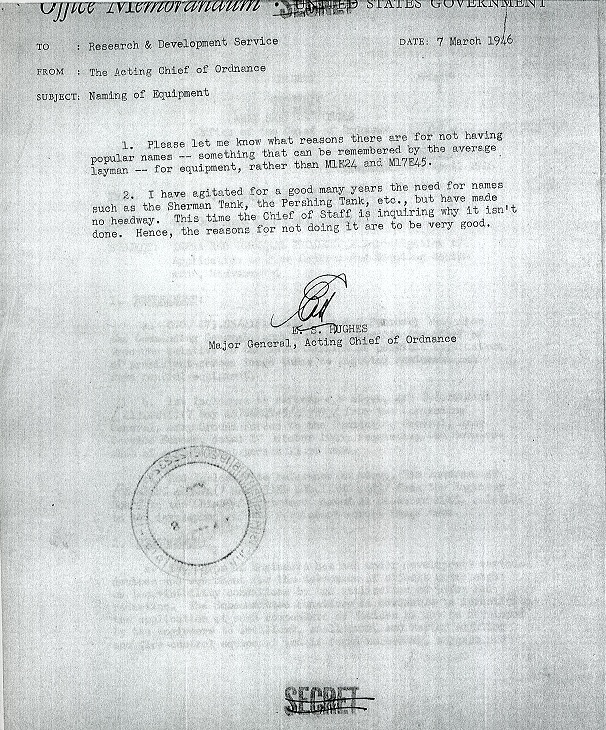

If you're one of the folks who watched Operation Think Tank's Episode 7, the first segment of the afternoon session, you'll know that the question was asked “where did the names of tanks come from?” An entertaining 15 minutes or so was spent discussing this matter. David Fletcher got us off to a good start, he saw the original document which started the whole “General Lee, General Stuart, etc." business. But there is a proviso: He is very specific that the word “General” was not to be used. Somewhere along the line, “General” got added, but nobody seems to know where. Ken Estes points out a post-war document in which the US Chief of Ordnance is asking why we don’t routinely name things in a similar manner to “Sherman” or “Pershing”. This is the document in question:

On the German side, “Hetzer” and “Brummbar” get a fairly definitive slating, and pretty much everyone is in agreement that there was no US recognition of names like Sherman, Jackson etc until Chaffee, with some hypothesis being given to the influence of modellers, or simply post-war recognition, even though there were occasional instances of official US use such as a reference in a US Intel bulletin in early 1944 to Panther being “similar to our own General Sherman”

Turns out there is, at least for the American side, a bit of a problem.

Some very knowledgeable wrong people.

Some very knowledgeable wrong people.

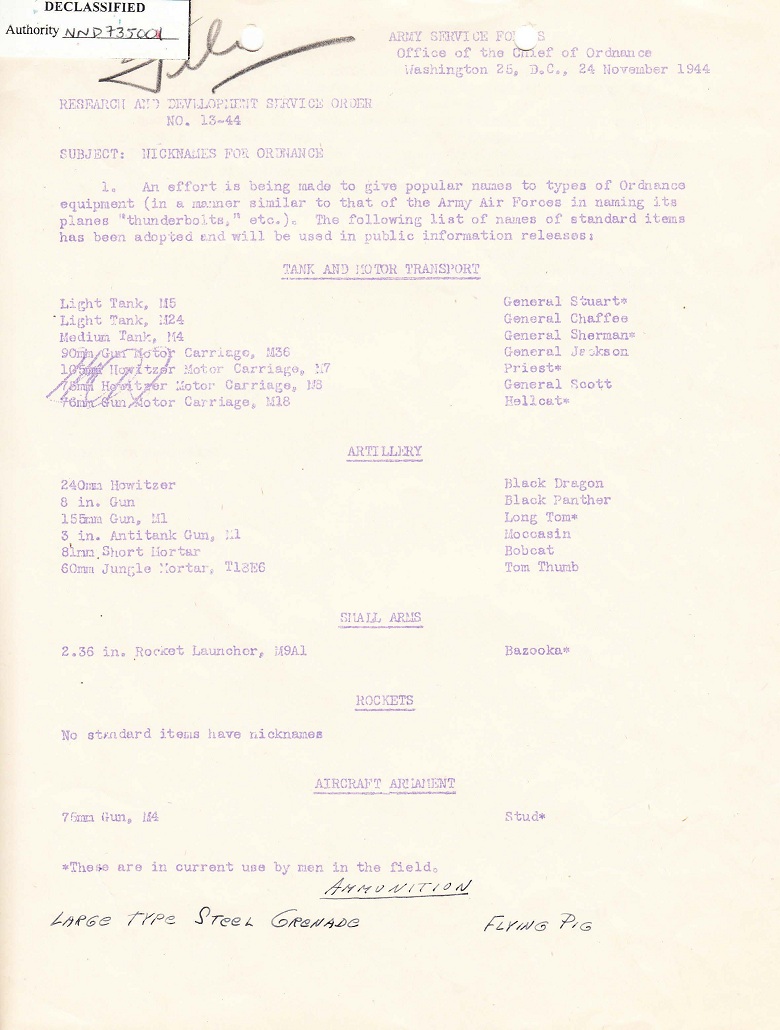

It is known that it is often impossible to prove a negative. Well, we can now at least somewhat disprove it with a positive. I mentioned in my article about the US National Archives how they’re a bit of a mess and you end up sortof diving into boxes at random. Sometimes you find something unexpected and interesting. I’ll just put the first document up.

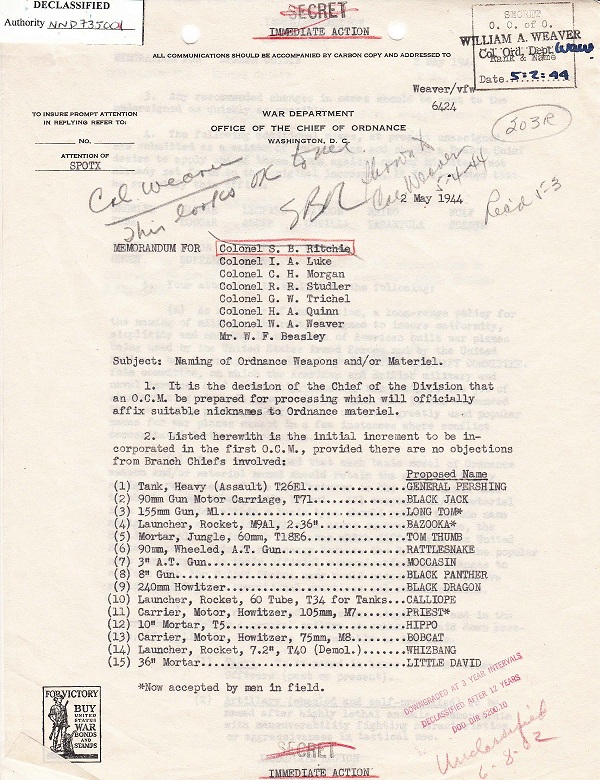

There are a couple of things to note, here.

Firstly, of course, this is only a proposal document. Secondly, the only “British” name on the list is “Priest”. Thirdly, you can see the official sanction being proposed for the first “General” name, with “General Pershing”, with the naming of tanks after general officers as a policy being proposed.

Other points of interest: It is a proposal for future US naming only. It specifically points out that if the British already have a name for something and the US name is different, the different names should be retained. The impetus for this appears to be the aircraft industry which makes some sense: Britain and the US often had differing names for aircraft (e.g. Kittyhawk/Warhawk) , while the US didn’t give its ground equipment names to cause confusion with in the first place.

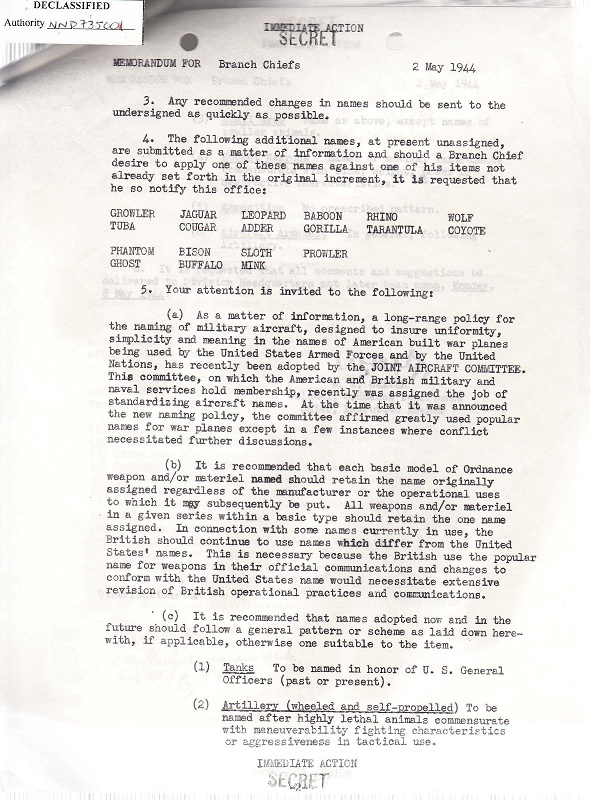

I'm certainly amused by the ‘available’ names. Artillery, Small arms and aircraft armament, it says, are the ones to be named after highly lethal animals. Artillery get big animals, small arms small animals. Exactly how “Sloth” meets the definition of “highly lethal animal” I’m not sure. I certainly couldn’t take any weapon named “Baboon” seriously, regardless of how vicious the real animals are.

The last notable is the proposed name for the 90mm Gun Motor Carriage T71. This is the vehicle which would become standardized as the M36 tank destroyer. As an alternative to blaming the model companies, it has been proposed by various sources (usually on the web) that the reason “Jackson” came out as a common name is because it was the British name for the thing, and followed with British naming convention of civil war generals. I never took much stock in this: The British never used the vehicle, so why they would name it anything at all to begin with? Of course, no authoritative references are provided.

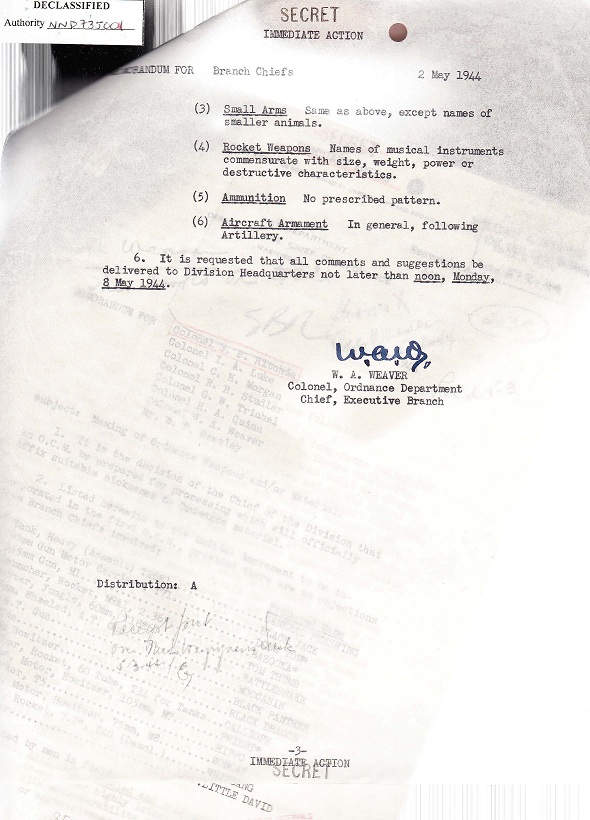

Oh, and the turnaround for responses to be received was 8th May, six days after the memo was sent out to begin with. A reasonably short suspense in the days before email.

But wait! There’s more.

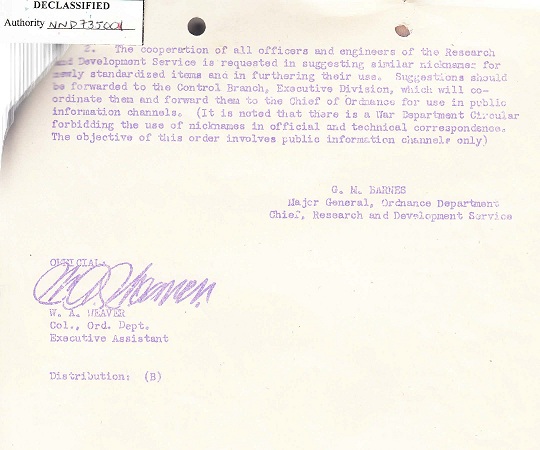

Further digging (actually, the next file) provided the following document from November 1944. Note now that the verbiage has changed to “the list of names […] has been adopted and will be used in public information released.”

Some things are immediately obvious.

Firstly, we now have a reasonably definitive answer to the question of putting “General” in front of the tank names: For some reason we’d always been assuming it was the British that gave us the common term “General Sherman”, but it seems it was the US Army that started it. No indication of “Lee” or “Grant”, though. Presumably because by that stage they were pretty much gone from US inventory and there was no point in wasting any ink over them.

Secondly, we now have an answer to the “Jackson” question. That, too, was the US Army and unlike Sherman or Stuart, it was a name selected by Ordnance as it wasn't in use with the troops. There is no explanation of the change from Black Jack to General Jackson, but since Pershing’s nickname was Black Jack, if there was already a Pershing vehicle perhaps it was viewed as duplication. “Hellcat” is getting official sanction as well, so Buick’s PR team has been proven totally awesome. That the Army would accept the Hellcat name (as well as Bazooka, Long Tom and others) already in use instead of trying to enforce a change to fit with a naming convention and add confusion was a rare bit of common sense.

Now, you’ll note the bit in brackets at the very end about not using nicknames in official documentation. I wouldn’t read too much from this, as it’s a policy basically in effect today. You will rarely find Army documentation such as a field manual which refers to the M60 or M1 as anything other than M60 or M1. (Though, granted, the TM says “General Abrams” on the cover), and in any case, a policy forbidding the use of nicknames does not deny the actual assignment of nicknames.

There is one very obvious and disappointing omission here, however, that being the 3" GMC M10. I have never been a supporter of the name “Wolverine”, and though it’s commonly stated on websites, I have seen no War Office documentation to support the proposal that it was a British name. Further, it fits in with neither the British policy on naming US tanks, nor on their policies of naming artillery pieces after the clergy or the letter “A.” Even “Achilles” didn’t show up as a name until very late in the war. Now, that said, there are two reasonable arguments in favour of the name. Firstly, a wolverine is arguably an animal of some lethality and so would fit in with the idea of it being the name for a US artillery piece, as a gun motor carriage. However, the assignment of “General Jackson” and "General Scott" indicates a classification for naming purposes of a motor carriage as a tank, so a “General” name would presumably have been selected. The other possibility, which I have seen nothing to confirm, but similarly cannot disprove, is that it is a name given by the Canadians, who tended to name all their vehicles after animals. Even their M4 Mediums were named “Grizzly” so they evidently had no issues with going their own way.

The last thing I’ll say on the subject of names right now is to direct your attention to this excellent post on the forum, describing the rationale behind the naming of Japanese tanks in the war.

So there you have it. Ordnance did officially assign “General” names to its tanks during the war, including the M36. I was one of the people sitting up on the stage, confident in the fact that our pronouncements were correct. As far as anyone knew at the time, they were. The important thing is that as new information comes available, we do not stand on our pride, accept that we were wrong, and then do what we can to redress the misconceptions.

Oh, by the way, in addition to my Facebook page, I'm starting up a Twitter feed.

Update comments

Update comments