Back to Harry for the conclusion of his overview of the US Army's tank doctrine in the Pacific theatre. - The Chieftain

Article by Harry Yeide

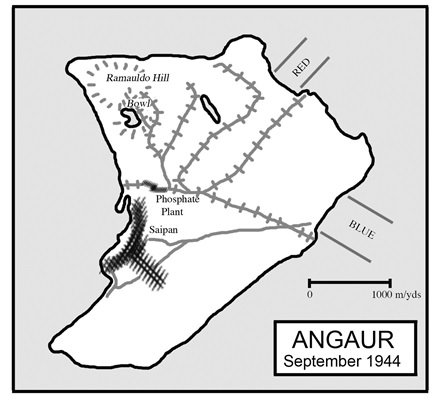

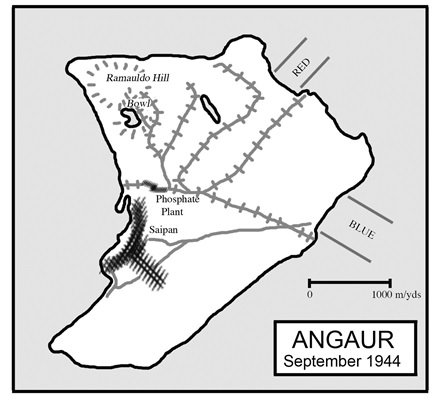

Angaur and a Big Hole

Fleet operations in the central Pacific in early September revealed that Japanese strength was far weaker than expected, and commanders decided to move more directly than they had intended into the Philippines. MacArthur and Nimitz nevertheless believed that they could not bypass the Palau Islands, because they judged they would need air bases there to protect lines of communications to the western Pacific.[i] The two first objectives would be two islands that lay cheek-by-jowl: Angaur, which fell to elements of the Army’s 81st Infantry Division, and Peleliu, which went to the 1st Marine Division.

The invasion force headed for shore about 0815 hours, with amtanks arrayed on the flanks of the first two waves. Resistance at the beach was surprisingly light, consisting only of small-arms and mortar fire. The amtracs deposited their loads of infantry without a single loss. The amtanks on Blue Beach worked inland with the infantry as planned and stuck with them until noon on D plus 1. A natural barrier trapped the tanks on Red Beach, where one officer was killed, and by the time engineers had built a road, land tanks from the 710th Tank Battalion had arrived.[ii]

For the 710th Tank Battalion, in the words of its commanding officer, Lt. Col. W. M. Rodgers, "tanks of the 710th were used under adverse conditions of terrain and weather during a period of groping and ‘cut and try’ developments in so far as the use of armor in the Pacific was concerned." Tank operations were on the scale of platoons or sections supporting infantry companies. Fortunately, the battalion and infantry had trained extensively together, each tank company with the regiment beside which it was going to fight, and techniques developed on Oahu worked well. Rodgers described the battle for the island as “hard, slow, bitter fighting.”

The battalion’s after-action report for 18 September offers a representative vignette: “Because of the extremely heavy jungle growth, it was necessary for the tanks to shoot into the jungle with .30-caliber machine guns and 75mm guns, blasting the foliage away to afford visibility. The infantry followed the tanks [by] from twenty-five to fifty yards... In firing into the jungle growth... , each tank took an area and searched it; while enemy troops were seldom seen, upon moving forward many dead Japanese were found in the areas fired upon, and in no case had the enemy succeeded in getting close to the tanks with any kind of demolition or antitank mines.”[iii]

Rodgers observed that because most actions involved two or three tanks, it was hard to construct a history of the fight on Angaur. Corporal Edward Luzinas, gunner in a platoon leader’s M4A3 in Company C, left one account of his platoon’s attempt to support an infantry attack on 21 September into the Lake Salome bowl below Ramauldo Hill, the dominating terrain feature on the northwest corner of the island, where the Japanese had built their key strong point. The “Angaur Bowl,” as it became known to the 81st Division, was surrounded by cliffs cut by a single rail line for a narrow-gauge mine train. Inside the gap, an embankment of diggings bore the rail line down to the lake.

Heavy Japanese fire stopped the GIs the first time they tried to follow the tanks through the gap, but after liberal doses of friendly artillery and mortar fire, the advance resumed. Intelligence had told the tankers that the Japanese lacked guns that could hurt their tanks, but as the M4A3s crunched through the cut, they found the way blocked by a self-propelled gun that had been knocked out by something. After failing to remove the wreck kinetically (shells, satchel charges), the tankers towed the gun out of the way, the tanks set off down the embankment.

Something hit Luzinas’s tank, which was in the lead, and paint chips flew around the turret. The Japanese gun in fact did not penetrate the armor, but shells worked over the suspension and tracks on the three tanks stretched out down the embankment. The infantry was stymied.

Luzinas spotted the gun in a cave through his periscope as it fired, emitting a cloud of yellow, brown, and gray smoke. He sprayed the entrance with .30-caliber fire. The tank commander asked him what he was doing, and after Luzinas explained, told him to knock the gun out. Eight rounds of HE did the trick.

The infantry moved in, but it was now so close to sundown that the commander did not want to risk being cut off in the bowl by a counterattack after dark, and he ordered a withdrawal. That meant the tanks had to back up the embankment, and steering a tank backwards was no easy task on a flat road.

The two tanks to the rear tried, and each tipped over the side, carrying chunks of the ramp with them. Japanese fire chased the crewmen as they ran for safety, and one man was wounded.

A fourth tank was in the cut, but Luzinas’s commander had little faith in relying on directions from there to maneuver. There was, however, the infantry phone on the back of the tank. The loader volunteered to go and slipped out the escape hatch in the belly of the tank. Sheltering as best he could, he directed the driver safely and slowly back up the long embankment to the cut. When a sniper opened up from a palm tree to the rear, the loader pointed Luzinas to the target, and after searching fire from the coax, the shooting stopped.

They don’t teach that at Ft. Knox.

The next morning, the crew discovered that the Japanese gun had badly damaged the suspension, and only one connector was holding the track together. Luzinas pondered religious thoughts.[iv]

* * *

The 710th Tank Battalion relied mainly on liaison personnel with SCR-536 and SCR-509 radios to talk to the infantry. The battalion had put field telephones on the backs of its tanks, but it found that GIs under fire did not replace the handsets, and they were torn off when the tanks moved. The battalion replaced its 105mm howitzers with M10 tank destroyers for the operation, judging the 3-inch gun to have greater penetrating power at longer range.

The battalion had to sit out the last phase of the battle for Angaur from 7 to 22 October because the terrain on the northern tip of the island was too rough for tanks. Company A and other battalion elements moved to Peleliu on 22 September with the 321st Infantry to assist the Marines in their bitter fight against the 14th Japanese Division.

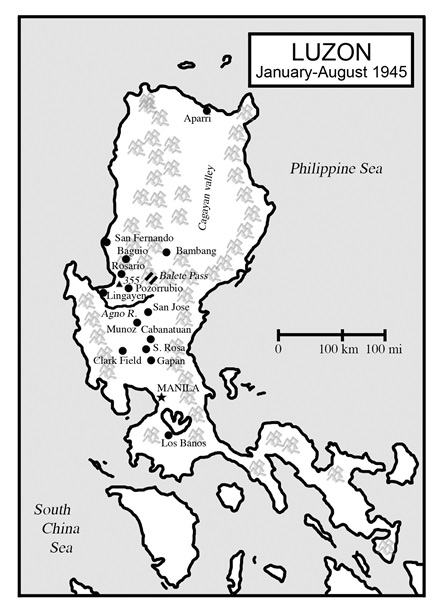

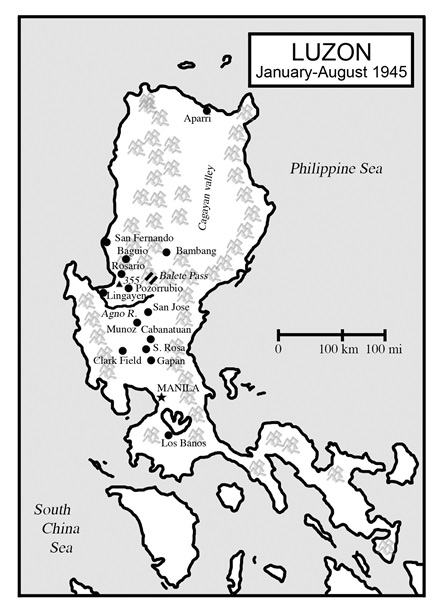

The Drive into Northern Luzon

Tank operations during the drive into the Cagayan valley in northern Luzon in early 1945 were probably the most diffuse of any organized corps-scale campaign during the war. Except on the valley floor, the terrain was mountainous and jungle clad, and opportunities for even platoon-sized action were rare. The 775th Tank Battalion in April, for example, had its headquarters and Companies C and D attached to the 25th Infantry Division, which was driving through the Balete pass into the Cagayan valley to eventually link up with the 11th Airborne Division at Appari; Company B attached to the 37th Infantry Division, which was advancing on Baguio; Company A attached to the 33d Infantry Division, also attacking toward Baguio.

Tanks often had to support infantry attacks against Japanese pillboxes and gun positions hidden in literally trackless, sloped jungle. Bulldozers had to create “roads,” or the tanks had to smash through the vegetation on their own.[v]

The 25th Division’s 27th Infantry Regiment recorded a representative picture of the setting and the role of the tanks:

Some three thousand yards south of Ba1ete Pass, the gateway to the Cagayan valley, the enemy constructed his main line of resistance. These defenses formed a general east-west series of fortifications extending from a right f1ank west of Highway 5 to some distance beyond the Old Spanish Trail, which parallels Highway 5 approximately 12,000 yards to the east.

To man this main line of resistance, the enemy had formed a provisional force composed of elements of his main infantry reinforced by various service units collected from all sectors of Luzon. Principal enemy units represented were the 10th, 11th, and 63d Infantry regiments; the 10th Engineer Regiment; the 10th Transportation Regiment; the 8th Railroad Regiment; and artillery from the 10th Division reinforced by independent artillery and heavy mortar units.

The terrain south of Balete Pass was especia1ly suited for defense. Perpendicular to Highway 5, the enemy's defenses were constructed along a series of ridges and principal hill-masses to which there were few natural routes of approach. The central anchor of the main line of resistance was formed on Myoko Mountain, the dominating hill-mass of the entire area south of Balete Pass and north of Putlan. . . .

With the 2d Battalion in the lead, the regiment commenced the advance to the north. Company G was assigned the left sector adjacent to the highway, and Companies E and F were directed toward Myoko. The terrain was characterized by steep slopes covered by dense rain forest, which offered many problems and hardships in both maneuver and supply. The enemy was supported by intense mortar and automatic weapon fire, and his riflemen were well dug-in on commanding ground. . . .

The terrain was not “tank country.” Rather than the usual flat or gently rolling ground usually associated with armor, Myoko Mountain offered only the sharp, narrow ridgeline to the northeast. Saddles and knolls were impassable, and bulldozers had to cut paths, often pushing the tanks into position. . . . When terrain was reached over which the tanks could not move, infantrymen moved ahead to secure the next favorable ground, and the bulldozers followed to improve the ground for further employment of the tanks. Often the path of the tanks was so narrow that a small portion of each track extended over the edge of the ridge.[vi]

Lieutenant Colonel Eben Swift described how his 3d Battalion, 27th Infantry, put just a few 775th Tank Battalion Shermans to work in early April to take a feature nicknamed “the Pimple,” the highest point on the main Myoko hill-mass. The Japanese were dug in and supported by 150mm and 90mm guns.

A Sherman from Company B, 775th Tank Battalion, works with 37th Infantry Division doughboys on 12 June 1945 in Luzon’s Cagayan valley, Philippines. The tankers proved they could work in rugged jungle terrain that nobody had ever imagined at the start of the war. (Signal Corps photo)

Swift obtained an armored bulldozer and cut a trail to the Japanese main line of resistance, opening the way for two Shermans that advanced protected by infantry against Japanese suicide attacks. Swift described the scene:

The tanks labored forward up the narrow bulldozer road to the crest. The Japs knew that something was in the wind and dropped mortar fire; however, most of it passed harmlessly overhead and exploded in the draw behind the tanks. The first tank reached the end of the road almost at the crest of the knoll but stalled when it reached the lip projecting from the crest. . . . The tracks started spinning in the soft dirt. . . .

The bulldozer crawled up behind the tank and pushed it over the top as both engines roared and sputtered. The tank maneuvered into position and fired its 75 and machine guns point-blank at the Jap positions on the Pimple. As fast as the Japs crawled out of their foxholes to fire at the tank, our BAR and rifles cut them down. The 75s not only knocked out the enemy’s pillboxes, but also blasted away undergrowth and camouflage in front so they could be plainly seen. After the first tank was set, the bulldozer pushed the next tank up. Together, the two tanks and Company B’s riflemen methodically plastered the area.

The next day, the battalion kept two Shermans on a nearby hill firing continuously all day long as the riflemen dug the Japanese off the objective. When one ran out of ammunition, it would pull back and the other would take its place. At the end off the day, commented Swift, “We had squeezed the Pimple.”[vii]

The regiment noted regarding its advance, “The psychological effect [of tanks] on the enemy was very strong, and the absence of antitank guns proved that he had not remotely expected or considered that tanks could be employed in this sector. . . . [T]he support of the medium tanks was invaluable.”[viii]

The 775th Tank Battalion concluded at the end of the campaign in northern Luzon, “No one ever conceived that [medium tanks] would or could operate over the rugged terrain which characterized most of the fighting after the enemy was beaten from the central plain into the mountains.”

Further Reading

See my website: World War II History by Harry Yeide

See the book from which this article derives: The Infantry's Armor

References

[i] Smith, The Approach to the Philippines, 492.

[ii] AAR, Company D, 776th Amphibian Tank Battalion. AAR, 776th Amphibian Tank Battalion. History, 726th Amphibian Tractor Battalion. Capt. Jerry V. Keaveny, “Operations of Company A, 322d Infantry (81st Infantry Division) in the Cleanup Phase of the Capture of the Island of Angaur, 11-22 October 1944 (Western Pacific Campaign) (Personal Experience of a Company Commander),” submitted for the Advanced Infantry Officers Course, 1949-1950, the Infantry School, Fort Benning, Georgia.

[iii] AAR, 710th Tank Battalion.

[iv] Edward C. Luzinas, Tanker: Boys, Men, and Cowards (London: Athena Press, 2004), 71-79. (Hereafter Luzinas.)

[v] AAR, 775th Tank Battalion.

[vi] “Battle Report: Luzon Campaign, Twenty-Seventh United States Infantry,” reproduced at the 27th Infantry Regiment “Wolfhounds” website, http://www.kolchak.org/History/WWII/Luzon.htm, as of May 2007. (Hereafter “Battle Report: Luzon Campaign, Twenty-Seventh United States Infantry.”)

[vii] Lt. Col. Eben Swift, “Tanks Over the Mountains,” Infantry Journal, October 1945, 32-33.

[viii] “Battle Report: Luzon Campaign, Twenty-Seventh United States Infantry.”

Update comments

Update comments